Binge Eating Disorder and Suicide Peer Review Article

- Research commodity

- Open Admission

- Published:

The relationship between body mass alphabetize, rampage eating disorder and suicidality

BMC Psychiatry volume 18, Article number:196 (2018) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

While restrictive and compensatory eating disorders (east.k. anorexia and bulimia) are associated with elevated run a risk of suicide, less is known most rampage eating disorder (BED). There is suggestive evidence of a U-shaped relationship between body mass index (BMI) and completed suicide, but fewer studies on suicidal ideation or attempts. This study examined the association betwixt BED, BMI, and suicidality, and assessed whether these relationships varied by gender.

Methods

Information come from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiologic Surveys (N = 14,497). Rampage episodes and BED were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Inventory (CIDI). BMI was calculated from self-reported pinnacle and weight. Suicidal ideation/attempts were assessed using the CIDI. Weighted logistic regression was used to assess the association between binging/BED, BMI and suicidality. Interaction terms were used to assess whether the relationship between BMI and suicidality was moderated by binging/BED, and whether the relationships betwixt binging/BED and BMI differed by gender.

Results

One-third of adults with BED had a history of suicidality, compared to 19% of those without. Both binging (OR: one.95, 95% CI: 1.fifty–2.53) and BED (OR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.41–2.86) were associated with suicidality in fully-adjusted models. BMI was associated with suicidality in a curvilinear way, and this relationship was exacerbated by binging/BED (ORBinge eating x BMI: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.09, p < 0.05). The human relationship betwixt BMI and suicidality did not differ by gender (ORgender ten BMI: 1.00, p < 0.770). However, the relationship betwixt binge eating and suicidality was stronger for women relative to men (ORgender X binge: 1.87, p < 0.012).

Conclusions

Binge eating, even beneath the threshold for BED, is associated with suicidality. BMI is associated with suicidality in a curvilinear manner, and the BMI-suicidality relationship is potentiated by rampage eating/BED. Findings support the thoughtful integration of psychiatric intendance into weight loss programs for adults with a history of binging behavior.

Groundwork

Binge Eating Disorder (BED) is characterized by consuming large amounts of food in a short catamenia of fourth dimension with a marked loss of control [1]. BED is the most mutual eating disorder in the United States (lifetime prevalence: three.5% for women and 2% for men, although some estimates range every bit high as 8%) [one, 2]. Relatively petty is known about the class and correlates of this condition equally compared to other eating disorders (i.e., anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa) as BED was only included as a singled-out diagnostic category in the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Transmission of Mental Disorders (DSM) [3].

Eating disorders, including BED, are often co-morbid with other forms of psychopathology. For example, adults with BED report higher levels of broken-hearted and depressive symptomology compared to adults without BED [4]. As with psychopathology in general, eating disorders are associated with elevated adventure of suicidal behavior [4,v,6,7]. For example, numerous epidemiologic studies have shown that anorexia and bulimia nervosa are associated with adventure of both attempted and completed suicide; [4, half dozen] still, merely a scattering of studies have examined the relationship between BED and suicidal behaviors [4, 8]. In a study of women drawn from the Swedish registries, Pisetsky and colleagues (2013) reported that the take a chance of attempted suicide associated with BED was elevated similar to other eating disorders, although this gauge was based on only 64 cases of BED [v]. In their meta-analysis, Preti et al. (2010) reported that BED was not associated with completed suicide, although this was also based on a relatively small number of cases [vi]. Finally, a more than recent study past Suokas et al. (2013) using Finnish registry data reported that suicide mortality was non elevated amongst persons treated for BED [7]. To our noesis, the human relationship betwixt BED and suicidality has not been examined in a population-based sample of U.s.a. adults.

The relationship between obesity and psychopathology is complex and remains poorly understood [ix]. Different other eating disorders (i.due east. bulimia, anorexia), individuals with BED do not appoint in restrictive or compensatory behaviors (e.g., excessive exercise, laxatives, vomiting). Every bit a event, individuals with BED are at a higher risk for gaining weight and developing obesity. While most studies bespeak that extreme obesity (i.e., BMI ≥ 35 kg/thou2) is positively associated with depression and other forms of psychopathology, [10,eleven,12,13] several reports suggest that the relationship betwixt BMI and psychopathology is non-linear. For example, most studies written report little or no difference in the prevalence of low for BMI in the overweight and form 1 obesity range (i.e., BMI between 25 kg/m2 and 35 kg/m2) relative to normal weight, [11, 12, fourteen] and several reports indicate that overweight is associated with lower likelihood of depression relative to normal or underweight [11, 13, 15, 16] especially for non-Hispanic white populations [17]. The human relationship betwixt depression and obesity likewise appears to exist more pronounced for women relative to men [18].

Consistent with this non-linear relationship between BMI and psychopathology, epidemiologic studies using mortality registries consistently study an inverse or inverted J-shaped relationship betwixt BMI and completed suicide, such that suicide risk is highest amidst individuals with BMI < 20 kg/m2 (and, ≥35 kg/mii, in those that report a J-shaped relationship), with lowest risk in the overweight and moderate obesity range [19,twenty,21,22,23,24]. A contempo meta-analysis of 38 population-based studies reported that underweight was associated with elevated risk of suicide, and that overweight and obesity were associated with significantly lower chance of suicide, relative to normal weight [25]. While a handful of smaller studies betoken that extreme obesity (BMI ≥ xl kg/m2) is positively associated with suicidal behavior, [25, 26] most studies written report an changed linear relationship with BMI and suicidal ideation and attempts [26, 27]. Like to the relationship between depression and obesity, in that location is suggestive evidence that this relationship between BMI and suicide may vary past gender [28]. Withal, few, if any, of these studies of BMI and completed suicide accept accounted for history of eating disorders.

Suicide prevention requires the identification of novel risk factors for suicidal behaviors. Few big, population-based studies have examined whether rampage eating beliefs contributes to the relationship between BMI and suicidality. To this end, and edifice on prior research, the aim of this study was to make up one's mind the association between binge eating/BED, BMI and suicidality (i.due east., ideation and attempts). We evaluated three hypotheses: (1) BED is associated with elevated likelihood of suicidality, (2) BMI is associated with likelihood of suicidality in a non-linear manner, and (3) The relationship between BED and suicidality is exacerbated past BMI. We as well explored whether these relationships differed by gender.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Data are from the 2001–2003 Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiologic Surveys (CPES). The CPES is a set of iii nationally-representative cantankerous-sectional householdsurveys (The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), The National Survey of American Life (NSAL), and the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS)) conducted to estimate the prevalence of psychopathology in the developed (age ≥ xviii) population and to assess treatment patterns, with specific attention to racial/ethnic minorities [29,thirty,31]. Boosted details nigh the CPES study design and sampling arroyo are described elsewhere [29,30,31]. The CPES information used for this analysis are available through the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Enquiry: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/20240.

This analysis was limited to individuals with complete information on BMI, BED, and suicidality (North = 14,497), which represents 72% of the total CPES sample. Those excluded from the analytic sample (Northward = 5516) were older, more likely to be male, more likely to be white, and had more education than those included; poverty-to-income ratio and BMI were similar (Additional file 1: Table S1). Most of those excluded were from the NCS-R, which past design merely asked the complete set of BED items on a random subset of 2980 participants [32].

Measures

Exposure ascertainment

Lifetime history of BED (with hierarchy) was assessed using the World Wellness Organization'southward (WHO) expanded version of the Blended International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for DSM-IV [2]. BED example condition was indicated if respondents endorsed binge eating, defined equally (a) recurrent episodes of eating, in a discrete (2-h) menses, an corporeality of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar catamenia of time accompanied by (b) a sense of lack of control over eating, and (c) 3 or more cerebral or affective feelings during the binge (i.due east., eating rapidly, eating until uncomfortably full, eating when non feeling hungry, eating alone due to feeling embarrassed by the amount of food consumed, feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty after overeating, or marked distress). These binge episodes had to occur at least 2 days a week for 6 months, and the binging could not be associated with use of compensatory behaviors (i.e. purging, fasting, excessive do), consistent with DSM-IV criteria. Individuals with bulimia or anorexia nervosa were excluded from the BED bureaucracy diagnosis. Lifetime history of any binge episode was defined as criteria a and b only, and with duration of ii days/week for at least three months. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated from self-reported weight and height. It was treated as a continuous variable (centered on the sample hateful: 27 kg/m2). As a sensitivity analysis we too evaluated BMI every bit a chiselled variable using WHO categories (< 18.five, 18.5 to < 25 (reference group), 25.0 to < thirty and ≥ xxx).

Event ascertainment

Lifetime suicidality was indexed past a CIDI module that assessed suicidal ideation / intent (i.east., "seriously thought about committing suicide" or "made a plan for committing suicide") and suicide try, including the age of onset and recency of suicidality. For this assay 2 dichotomous variables were created: for the master assay we examined lifetime (e'er/never) suicidality (ideation and/or intent), and for the sensitivity analyses we examined by-year suicidality; for the sensitivity analysis individuals who endorsed suicidality only prior to the by year were excluded (due north = 2030).

We also conducted a post-hoc analysis examining lifetime history of attempting suicide as an outcome. Because of the skip-pattern of the CIDI, history of suicide effort was only asked of those who endorsed suicidality; yet, for this analysis we created a new variable indexing lifetime history of suicide attempt past recoding respondents who had not seriously considered suicide as a "no" for history of attempting suicide, equally prior studies of this outcome have done. Due to some missing data on the effort question, this analysis was limited to thirteen,079 respondents.

Covariates

All covariates were assessed by self-study and included age (in years, mean-centered at 43.4), race/ethnicity, gender, marital status, education and Income-to-needs ratio. Race/ethnicity was categorized as Asian, Hispanic, Black, and Non-Latino White, with Blackness as the reference grouping. Education was categorized as high school education or less (reference group) vs. more than high school. Marital status was categorized as currently married (reference grouping), formerly married, and never married. Income-to-needs ratio is a measure of socioeconomic status calculated by dividing household income by the Census poverty threshold for that household size, [33] categorized into quintiles. We as well considered smoking and medical comorbidities as confounders. Lifetime history of medical conditions (including arthritis, chronic pain, headaches, stroke, heart disease, hypertension, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and cancer) were summed and was categorized as zero (reference group), ane, ii, and 3 or more than weather condition for analysis. Smoking condition was available on a subset of participants (N = 9648) and was categorized every bit electric current, former, and never smoker (reference group).

Analytic approach

Initial bivariate relationships betwixt BED, suicidality and covariates were assessed using Scott-Rao chi-square tests. To address the first hypothesis, weighted logistic regression models were fit to test the association betwixt binge eating behavior and lifetime history of suicidality as the dependent variable. Three nested models were fit for both BED and binge episodes: Model 1 was unadjusted, Model 2 was adjusted for BMI. Model iii was adapted for BMI and sociodemographic characteristics, and Model four was additionally adjusted for number of chronic health atmospheric condition; nosotros besides fit models additionally adjusted for smoking status as a sensitivity analysis. Weighted logistic regression models were fit to assess the relationship between BMI and suicidality using a like nested model approach. To examination the 2d hypothesis, we evaluated whether a quadratic term on BMI improved model fit, indicating a curvilinear human relationship with suicidality. To test the third hypothesis, logistic regression models were fit that included interaction terms between BED (and binge eating) and BMI. To evaluate whether these relationships were like for men and women these models were then fit within strata of sexual activity. Equally a sensitivity analysis, all models were refit to examine the relationship between BED, binge eating, and BMI with by-year suicidality. Finally, we conducted two post-hoc sensitivity analyses: get-go, nosotros refit all models examining binge eating as the exposure while excluding the 271 cases of BED from the analysis; and second, we refit all models to examine the outcome of lifetime history of suicide attempt rather than suicidality.

Goodness-of-fit was assessed using the Wald test. All analyses were conducted using STATA/IC 11.2 survey procedures to account for the complex sampling design and all p-values refer to two-tailed tests.

Results

Approximately four% of adults had a lifetime history of rampage eating and 1.9% had a history of BED (48% of those who had history of bingeing) (Table 1). Respondents with BED were younger, predominantly female and were more probable to have obesity relative to those without BED. Approximately twenty% had a lifetime history of suicidality, with iv.0% in the by year, and 7.8% had attempted suicide at some indicate in their life. Among those with a history of binge eating, ane-third (34.2%) reported ever thinking about suicide, nearly one in five (18.6%) had always attempted suicide, and 10.1% experienced suicidality in the past year. These proportions were similar (37.5, 20.5 and eight.9%, respectively) for BED. BMI was strongly right-skewed, and overall 26% of respondents had a BMI in the obesity range.

Apropos the get-go hypothesis, both binge eating (Crude Odds Ratio [OR]: 2.21, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: one.67–2.92, p < 0.001; Adapted OR (AOR): i.95, 95% CI: 1.50–ii.53, p < 0.001) and BED (Crude OR: two.51, 95% CI: 1.79–iii.50, p < 0.001; AOR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.41–ii.86, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with lifetime suicidality (Tables 2 and iii). Adding BMI to these models did non substantially attenuate the human relationship between rampage eating/BED and suicidality. Findings from the post-hoc sensitivity analysis of excluding cases of BED from the models examining binge eating were consistent with these findings (Additional file one: Tabular array S2). Results were also similar when examining the outcome of by-year suicidality.

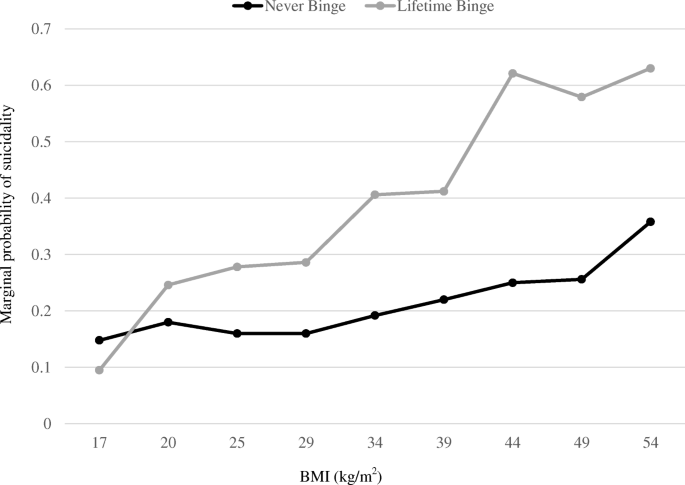

The quadratic term on BMI was meaning in the crude model (p < 0.004), and Fig. one illustrates the curvilinear relationship between BMI and lifetime suicidality by binge eating status. In that location was a small-scale but statistically significant relationship between BMI and suicidality (Boosted file 2: Figure. S1), which was influenced past both number of chronic conditions and smoking status (Additional file 1: Table S3). Modeling BMI as a 4-level categorical variable illustrated a similar non-linear human relationship with suicidality (Boosted file i: Table S4). These relationships were consistent when examining suicide attempts and past-year suicidality. Additional file 3: Figure S2 illustrates the curvilinear human relationship between BMI and past twelvemonth suicidality past lifetime binge eating status.

Probability of lifetime suicidality by lifetime binge eating behavior at select BMI. Marginal predicted probability of lifetime suicidal ideation/attempt by lifetime history of rampage eating beliefs past select BMI. Values are estimated at the sample hateful for all model covariates (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, income-to-needs ratio and chronic conditions). N = 14,497

Turning to the 3rd hypothesis, the interaction term between BMI and binge eating on likelihood of suicidality was statistically significant, even in fully-adjusted models (ORRampage eating x BMI: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01, ane.09, p < 0.021). The analysis of suicide attempt was similar (ORBinge eating x BMI: ane.07, 95% CI: one.01, 1.14, p < 0.018). This interaction is illustrated by Fig. 1, which shows that the relationship between rampage eating and suicidality was strongest for those with higher BMI. For instance, for adults with a BMI one standard deviation below the sample hateful (approximately twenty kg/m2) the relative odds of suicidality associated with binge eating was 1.38 (p = 0.136); notwithstanding, for those with a BMI 1.five standard deviation above the sample mean (approximately 34 kg/m2) the relative odds of suicidality associated with binge eating was 2.69 (p < 0.001).

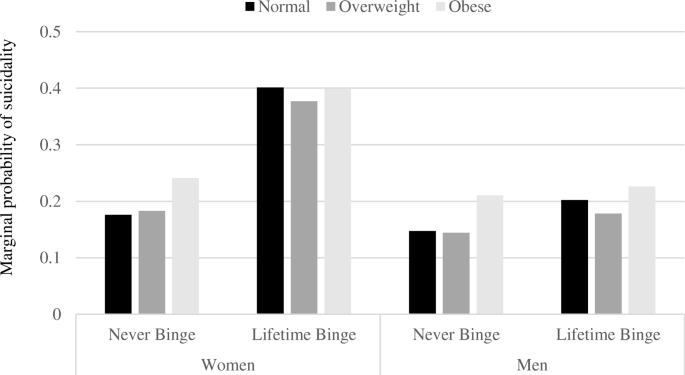

Finally, we examined whether these relationships were consistent for men and women. There was no evidence that the relationship between BMI and suicidality differed by gender (ORgender x BMI: ane.00, p < 0.770). Even so, the relationship between binge eating and suicidality was stronger for women relative to men (ORgender 10 rampage: 1.87, p < 0.012). Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between binge eating and lifetime suicidality by gender at normal, overweight and obesity levels of BMI from fully-adjusted models. Results from the post-hoc analysis of lifetime suicide attempt were similar (ORgender Ten rampage: two.66, p < 0.011).

Marginal probability of suicidality by gender and lifetime binge eating behavior. Marginal predicted probability of suicidal ideation/attempts by lifetime history of binge eating beliefs by gender and BMI category. Values are estimated at the sample hateful for all model covariates (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, income-to-needs ratio and chronic conditions). Due north = xiv,497

Discussion

The principal finding from this written report is that both binge eating behaviors and BMI are independently related to suicidal ideation and attempts among Us adults. The human relationship between BED and suicidality was non attenuated by BMI, indicating that BMI does not essentially explain the association between binge eating and suicidal behavior. Even so, there was evidence that the relationship betwixt binge eating/BED and suicidality was exacerbated by loftier BMI. Consistent with prior work on BMI and completed suicide, the human relationship between BMI and suicidality was non-linear, with highest run a risk associated with obesity relative to overweight, but with piffling difference in suicidality between underweight, normal, and overweight. These relationships were present for both genders, but the association betwixt binge eating and suicidality was stronger for women relative to men. To our noesis, this is the largest report to examine the relationship between BED, BMI, and suicidality in a diverse, nationally-representative sample of United states adults.

The finding that binge eating/BED is associated with suicidality is consistent with the broader literature on eating disorders and associated psychiatric comorbidities [eight]. Nearly one-3rd of women with BED report a lifetime history of suicidal Ideation and xv% had attempted suicide [34]. Several reports have linked rampage eating behaviors with mood disorders, [32] novelty-seeking, [35] and impulsiveness, [5, 36] which take in turn been linked to suicidal behaviors. To our knowledge, this study is the get-go to suggest that the relationship between binge eating and suicidality is moderated past BMI.

The linkages between BMI and suicidality are complex [24]. Nosotros found that the relationship between BMI and suicidality did not differ by gender, in contrast to several recent reports. Gao (2013) reported that the clan betwixt BMI and suicidality varied by gender and depression status, with an inverse relationship betwixt BMI and suicide attempts among men regardless of depression history; and a curvilinear relationship among women, with higher incidence of attempts among depression-BMI relative to normal weight women without history of depression, but a U-shared relationship amid women with depression [19]. Kim et al. (2016) too reported that the relationship betwixt BMI and suicidality was curvilinear and varied by gender in a big sample of Korean centre-aged adults [37]. Results from studies of BMI and suicidality amongst adolescent or young adult samples have generally been smaller and results are mixed [25, 38, 39].

Strengths and limitations

The cantankerous-sectional nature of our study precludes inferences regarding causality. However, our findings are consistent with prior literature on BED (and eating disorders more broadly) and suicidality, besides as BMI and completed suicide. Our analyses examining past-year suicidality and lifetime history of suicide attempt were consequent with our main results. BMI was calculated from self-reported weight and acme, which tends underestimate BMI; [40] individuals with eating disorders tend give a more accurate account of their weight, likely considering of greater weight-checking [40]. This analysis did non adjust for comorbid psychiatric weather (i.due east., major depression, general feet disorder) because these conditions are likely mediators of the BED (and potentially BMI) – suicidality relationship [32]. Finally, because of skip blueprint in the CIDI the questions on suicide attempt were only asked of those who reported ideation; while information technology is logical to assume that persons who have not seriously considered suicide would non accept attempted it, this may accept missed attempts that were more than impulsive in nature. This written report also has a number of strengths. The big, diverse, representative sample reduces the risk of option bias, BED was assessed using a reliable, structured diagnostic instrument, and the analysis deemed for medical comorbidities that likely derange the BMI-suicidality relationship.

Conclusions

Although more research is needed to decipher the circuitous relationships between BED, BMI, and suicidality, our findings can aid in understanding novel correlates of suicidality in the population. These findings complicate the ongoing debate about efforts to address eating disorders and the obesity endemic. With the adoption of BED in DSM-v, this will hopefully spur new conversations and debates almost the relationships betwixt weight, weight control messaging and interventions, and mental health.

Abbreviations

- BED:

-

Binge Eating Disorder

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CIDI:

-

Blended International Diagnostic Interview

- CPES:

-

Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiologic Surveys

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

-

Cossrow Due north, Pawaskar Yard, Witt EA, Ming EE, Victor TW, Herman BK, et al. Estimating the prevalence of binge eating disorder in a customs sample from the United states of america: comparing DSM-IV-TR and DSM-v criteria. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(eight):e968–74.

-

Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz Ac, Hudson JI, Shahly V, et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Wellness Organization earth mental health surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:904–14.

-

American Psychiatric Clan. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

-

Kostro K, Lerman JB, Attia E. The current status of suicide and self-injury in eating disorders: a narrative review. J Eat Disord. 2014;two:19.

-

Pisetsky East, Thornton L, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen N, Bulik C. Suicide attempts in women with eating disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:1042–56.

-

Preti A, Rocchi MBL, Sisti D, Camboni MV, Miotto P. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the run a risk of suicide in eating disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:vi–17.

-

Suokas JT, Suvisaari JM, Gissler M, Löfman R, Linna MS, Raevuori A, et al. Mortality in eating disorders: a follow-up study of developed eating disorder patients treated in third intendance, 1995–2010. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:1101–half-dozen.

-

Smith AR, Zuromski KL, Dodd DR. Eating disorders and suicidality: what we know, what we don't know, and suggestions for future research. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;22:63–7.

-

Ball Grand, Dark-brown W, Crawford D. Who does not gain weight? Prevalence and predictors of weight maintenance in immature women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:1570–8.

-

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BWJH, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Curvation Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220–9.

-

Ma J, Xiao L. Obesity and depression in US women: results from the 2005-2006 National Health and nutritional examination survey. Obesity (Silver Leap). 2010;xviii:347–53.

-

Onyike CU, Crum RM, Lee HB, Lyketsos CG, Eaton WW. Is obesity associated with major low? Results from the third National Health and nutrition test survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1139–47.

-

Zhao 1000, Ford ES, Dhingra Due south, Li C, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Depression and anxiety among United states of america adults: associations with body mass index. Int J Obes. 2009;33:257–66.

-

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Linde JA, Operskalski BH, Ichikawa L, Rohde P, et al. Association between obesity and low in center-aged women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:32–9.

-

Bjerkeset O, Romundstad P, Evans J, Gunnell D. Clan of developed trunk mass index and height with anxiety, depression, and suicide in the full general population: the Hunt report. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:193–202.

-

Goldney RD, Dunn KI, Air TM, Dal Grande E, Taylor AW. Relationships between body mass index, mental health, and suicidal ideation: population perspective using ii methods. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:652–viii.

-

Hicken MT, Lee H, Mezuk B, Kershaw KN, Rafferty J, Jackson JS. Racial and ethnic differences in the association between obesity and depression in women. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2013;22:445–52.

-

de Wit Fifty, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:230–v.

-

Gao S, Juhaeri J, Reshef S, Dai WS. Clan between trunk mass index and suicide, and suicide attempt among British adults: the wellness improvement network database. Obesity (Silver Jump). 2013;21:E334–42.

-

Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N. The human relationship of trunk weight to suicide risk amidst men and women: results from the US National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:948–51.

-

Magnusson PKE, Rasmussen F, Lawlor DA, Tynelius P, Gunnell D. Clan of body mass index with suicide mortality: a prospective accomplice written report of more than one million men. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1–8.

-

McCarthy JF, Ilgen MA, Austin K, Blow FC, Katz IR. Associations between trunk mass alphabetize and suicide in the veterans affairs health arrangement. Obesity (Silvery Spring). 2014;22:269–76.

-

Mukamal KJ, Kawachi I, Miller Yard, Rimm EB. Trunk mass index and chance of suicide amid men. Curvation Intern Med. 2007;167:468–75.

-

Perera S, Eisen RB, Dennis BB, Bawor M, Bhatt M, Bhatnagar Northward, et al. Body mass index is an of import predictor for suicide: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46:697–736.

-

Dutton GR, Bodell LP, Smith AR, Joiner TE. Examination of the human relationship between obesity and suicidal ideation. Int J Obes. 2013;37:1282–six.

-

Batty GD, Whitley Eastward, Kivimäki M, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Torso mass alphabetize and attempted suicide: cohort study of 1,133,019 Swedish men. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:890–9.

-

Sörberg A, Gunnell D, Falkstedt D, Allebeck P, Åberg M, Hemmingsson T. Body mass alphabetize in immature adulthood and suicidal behavior up to age 59 in a cohort of Swedish men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101213.

-

Zhang J, Yan F, Li Y, McKeown RE. Body mass index and suicidal behaviors: a critical review of epidemiological evidence. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:147–60.

-

Alegria M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, Duan Northward, Shrout P, Meng 10-L, et al. Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:208–20.

-

Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, et al. The National Survey of American life: a written report of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;xiii:196–207.

-

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): blueprint and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:69–92.

-

Forrest LN, Zuromski KL, Dodd DR, Smith AR. Suicidality in adolescents and adults with rampage-eating disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication and adolescent supplement. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:twoscore–9.

-

Proctor BD, Dalaker J. Poverty in the Us: 2001. Current Population Reports [Internet]. Superintendent of Documents, U; 2002 [cited 2022 Aug 30]. Available from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED469530

-

Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Curvation Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:714–23.

-

Grucza RA, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in a community sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:124–31.

-

Ural C, Belli H, Akbudak M, Solmaz A, Bektas ZD, Celebi F. Relation of binge eating disorder with impulsiveness in obese individuals. World J Psychiatry. 2017;seven:114–xx.

-

Kim D-K, Vocal HJ, Lee E-K, Kwon J-Due west. Effect of sex activity and historic period on the association between suicidal behaviour and obesity in Korean adults: a cross-sectional nationwide written report. BMJ Open. 2016;half-dozen:e010183.

-

Crow Southward, Eisenberg ME, Story Yard, Neumark-Sztainer D. Suicidal behavior in adolescents: human relationship to weight status, weight control behaviors, and body dissatisfaction. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:82–7.

-

Zuromski KL, Cero I, Witte TK, Zeng P. The quadratic relationship between trunk mass index and suicide ideation: a nonlinear analysis of indirect effects. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2017;47:155–67.

-

Barnes RD, White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Accuracy of self-reported weight and height and resulting trunk mass index amid obese binge eaters in primary intendance: human relationship with eating disorder and associated psychopathology. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12

Funding

The CPES was supported past the National Plant of Mental Wellness (U01-MH57716, U01-MH60220, U01-MH62209 and U01-MH62207) with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences, the Substance Corruption and Mental Health Services Assistants, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Academy of Michigan. This analysis was supported in part by NIMH (K01-MH093642-A1) and the American Diabetes Association (1–xvi-ICTS-082).

Availability of information and materials

The CPES data used for this analysis are available through the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/20240. umich.edu/icpsrweb/CPES/.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

KLB conceptualized the study, assisted with the analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BM assisted with the study design, conducted the analysis, and provided substantial input to the writing of the manuscript. JGL provided critical review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the concluding version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Ideals blessing and consent to participate

All participants in the CPES provided informed consent. This analysis used only publicly-bachelor data and thus was exempt from homo subjects regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file ane:

Table S1. Comparison of respondents excluded from main analysis due to missing data. Table S2. Relationship between binge eating and BMI and with suicidal behavior, excluding respondent with a history of BED. Tabular array S3. Human relationship between BMI and lifetime suicidal behavior, not accounting for binge eating behavior. Tabular array S4. Relationship between BMI categories and lifetime suicidal behavior, not accounting for binge eating. (DOCX 30 kb)

Boosted file 2:

Effigy S1. Probability of lifetime history of suicidality at select BMI. (DOCX 62 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S2. Probability of past-year suicidality by lifetime binge eating behavior at select. (DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the data made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Dark-brown, K.L., LaRose, J.G. & Mezuk, B. The relationship between body mass index, binge eating disorder and suicidality. BMC Psychiatry xviii, 196 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1766-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12888-018-1766-z

Keywords

- Suicide

- Binge eating disorder

- Population-based

- Gender

- Obesity

Source: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-018-1766-z

0 Response to "Binge Eating Disorder and Suicide Peer Review Article"

Postar um comentário